Flowage Easements

In the Spring of 1927, the Mississippi River, swollen with unusually heavy rains, overflowed its banks and inundated 27,000 square miles of land, making it one of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history. The entire Mississippi River levee system failed, with levees breached in at least 145 separate locations. Losses from the flooding have been estimated to be as high as $1 trillion dollars (in 2023 dollars).

The Mississippi Delta was devastated, with hundreds of thousands displaced and evacuated, having lost, in many cases, everything they owned. (An excellent exploration of the effects of the Great Flood on Mississippi and the social changes brought abought by the disaster, can be found in John M. Barry’s book, Rising Tide.)

In response, Congress passed the Flood Control Acts of 1928 and 1937 and charged the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at Vicksburg with developing a plan to reduce flooding in the Mississippi Delta. The Corps determined that to do so, it would be necessary to control the flow of water from the Yazoo River basin. The Corps’ plan resulted in the creation of Lake Arkabutla in Tate and DeSoto Counties, Lake Enid in Lafayette and Yalobusha counties, Sardis Lake in Panola County and Grenada Lake in Grenada and Yalobusha Counties.

Construction of the Arkabutla Dam, across the Coldwater River, was begun in 1940. In 1942, the entire Town of Coldwater, and its 700 residents, were relocated one mile to the south of its original location. The land comprising the bed of the lake was acquired by purchase or Eminent Domain, and, in addition, pursuant to the federal legislation, the Corps secured “Flowage Easements” from many landowners in the area surrounding the project.

The Corps defines a flowage easement as:

Flowage easement land is non-federal land on which the United States Government has acquired certain perpetual rights, including the right to overflow, flood and submerge the land, the right to prohibit structures for human habitation, and the right to approve all other structures proposed for construction within the flowage easement. The definition of structure also includes excavating or filling without the prior written consent of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

Here is a link to an example of a flowage easement. This one was acquired in 1942 for the Arkabutla project.

As can be seen from the above, these easements are severely restrictive and greatly impact the use of the land covered by the easement. For real estate practitioners, these easements present potential land mines. Many of them were acquired in the early 1940’s – well beyond the scope of most title searches. Some of the practitioners I spoke with in Tate County were generally aware of the existence of the easements in some areas, but couldn’t say they had actually ever seen any of the original instruments.

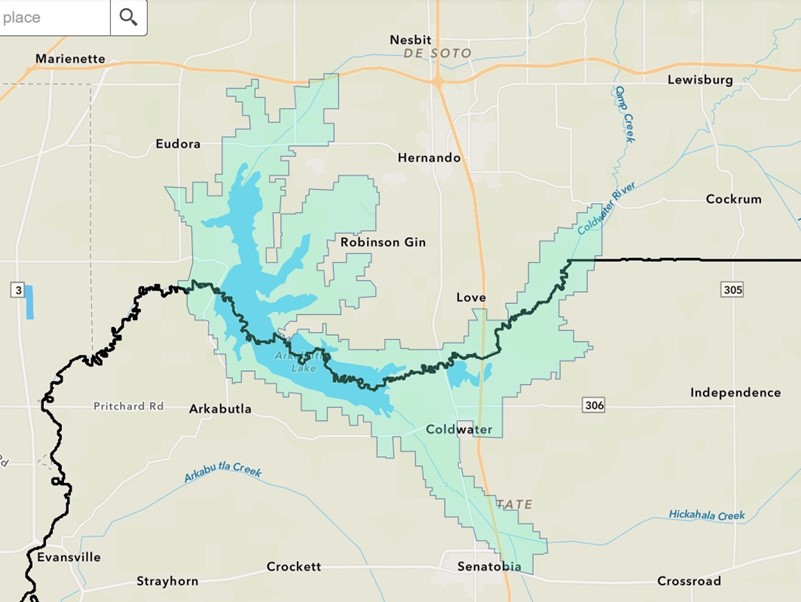

The Tate County Planning Commission’s website features an interactive map which gives a general indication of properties which are within the “flowage” area:

Those properties are within the light green area. The thick, black line indicates the boundary between Tate and DeSoto counties. Click here for the interactive map on Tate County Planning Commission’s website.

The top of the Arkabutla dam is 264.3 feet above mean sea level (“m.s.l.”). Most of the flowage easement “Perpetual Deeds” we reviewed cover property at, and below, the 242’ – 244’ m.s.l. range.

Our research has also identified a good number of more recent flowage easements at Sardis Lake in Panola County. Most of these appear to cover home sites at Lespedeza Point ( sometimes “Lespideza”). These appear to have been acquired in the late 1970’s early 1980’s. Here is a link to an example.

There appear to be few, if any, flowage easements in and around Enid Lake and Grenada Lake. The U.S. owns, in fee, a significant amount of land surrounding those lakes, which would obviate the need for the flowage easements.

I spoke with the Management & Disposal Branch of the Real Estate Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at Vicksburg and was advised that they can approve construction of non-habitable structures within a flowage easement area. Such requests should be submitted to:

Management & Disposal Branch

Real Estate Division

Vicksburg District, USACE

4155 Clay St.

Vicksburg, MS 39183

Lanny.C.Barfield@usace.army.mil

I was advised that the construction of habitable structures cannot be approved at the local level and that such approvals are rarely granted.

In summary, when handling transactions in the areas noted above, it is probably wise to ask your abstractor to look further back than usual for flowage easements. Especially, if your Client is wanting to construct a residence or a residential development of any kind. The area around Arkabutla Lake, in particular, has shown signs of development in recent years, and the flowage easements have come as an unpleasant surprise to many landowners. Here is a link to a DeSoto County Times article discussing the situation.