What to Know When Handling Transactions Involving Church-owned Property

In God’s Backyard

Key Items Title Agents Should Know as Churches Repurpose or Sell Land to Develop Affordable Housing

BY JEREMY YOHE

Jeremy Yohe is ALTA’s vice president of communications. He can be reached at jyohe@alta.org

As the United States continues to struggle to find solutions for affordable housing, more religious institutions all over the country are looking at selling church-owned land for the development of affordable housing. Some congregations are finding that repurposing or selling land can offer a financial benefit, while also expanding their social mission.

While it’s estimated there’s a shortage of over 4.5 million homes in the country, many states are adopting a YIGBY (Yes In God’s Backyard) approach by reforming laws and removing restrictive zoning laws that prohibit religious property from being put to any other use.

To transform properties into affordable housing, churches typically donate, lease or sell land (often at a discount) to nonprofit developers with experience building affordable apartments or homes. Those developers tap into some combination of donations, private financing and federal, state or local dollars to build and operate the housing. Developments sometimes include a new worship space for the church, though developers can’t use government housing dollars to build those spaces.

To help religious groups pursue housing projects, local and state lawmakers from California to Virginia have pursued legislation that fast-tracks projects on church-owned property. In 2021, the Biden administration created a Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships within the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

In 2019, Washington state passed a law incentivizing affordable housing development on property owned or controlled by religious groups, and local governments in Atlanta and San Antonio have started offering technical assistance to religious institutions interested in developing housing on their land. In Detroit, the city’s housing commission recently funded new affordable units on church property, and lawmakers in states like Hawaii and New York say they hope to follow in California’s footsteps with a YIGBY law.

In October 2023, California lawmakers passed legislation permitting religious organizations to bypass local permitting processes and eased zoning restrictions for development on property owned by religious organizations, making it easier for churches to build affordable housing. About 28% of the U.S.’s unhoused population live in California.

At the federal level, former Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) introduced the “Yes, in God’s Backyard Act” in March 2024. His “YIGBY” proposal would have provided technical assistance to faith organizations interested in building affordable housing.

Obstacles to Turning Churches Into Housing

What’s slowing the church-to-housing pipeline? Even God’s house has to abide by zoning laws. As more congregations study the idea of converting property, the unique challenges of such projects have become apparent, from lining up financing to overcoming the architectural incompatibility of the buildings themselves.

This landscape of faith is undergoing a dramatic transformation. In fact, it’s been estimated up to 100,000 houses of worship—a quarter of the estimated U.S. total—could shut over the coming decades.

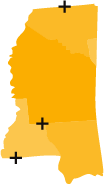

Church-owned Land

Bar height indicates acres owned by state (Alaska not shown)

A recent analysis by the Center for Geospatial Solutions at the Lincoln Institute found that religious groups own roughly 2.6 million acres across the U.S., with about 32,000 of those in transit-accessible urban areas. At the high end, that amount of land could supply 700,000-plus units of new housing, if subject to high-density development.

According to a 2023 study from the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley, faith-based organizations held more than 47,000 acres of land that could be potentially developed in California alone.

NYU Furman Center analyzed the zoning of land owned by faith-based organizations in New York City, detailing its scope and geographic spread. Faithbased organizations own more than 92 million square feet of land across the five boroughs. This is 2.5 times the size of Central Park.

Religious groups own roughly 2.6 million acres across the

U.S., according to the Center for Geospatial Solutions at

the Lincoln Institute.

In the D.C. metro area, the Urban Institute found almost 800 vacant parcels owned by religious organizations. In California, a report from the Terner Center found approximately 170,000 “potentially developable” acres of land owned by religious organizations and nonprofit colleges and universities.

In Seattle and other nearby cities, more than 2,000 units of housing on church property are at some stage of planning or construction, said Jess Blanch, Pacific Northwest program director for Enterprise Community Partners, an organization that helps churches plan and finance housing development.

Religious institutions of all faiths in Seattle, according to the city, own about 1% of land with various uses ranging from churches to schools and cemeteries. Most of that land is in neighborhoods previously zoned for single-family homes or low-rise development, according to the city. The Nehemiah Initiative, a nonprofit that offers training and predevelopment financial help to churches planning for affordable housing, estimates the city’s historically Black churches own about 75 acres of land that, if sold at market-rate prices, could be worth $200 million.

Development Remains Slow

In 2009, Arlington Presbyterian Church was celebrating more than a century in its Northern Virginia community. It was also facing another, less optimistic, milestone: The congregation, which had boasted more than 1,000 members in the 1950s, was down to fewer than 100. So, the church embarked on an unlikely resurrection.

Over the next decade, Arlington Presbyterian razed its main church and sold the land for $8.5 million—20% below market value—to the Arlington Partnership for Affordable Housing. The nonprofit then built Gilliam Place, a 173-unit affordable housing development.

It took nearly a decade and about $71 million from 14 different funding sources before the first tenants moved in.

In Colorado Gov. Jared Polis urged lawmakers to support legislation to make it easier for churches to build housing on land they own. During his 2025 State of the State address, Polis highlighted a 77-unit affordable housing project that was built on the property of Village at Solid Rock in Colorado Springs.

In Lake City, Wash., a Mennonite church housed in an old movie theater found a developer to replace its current space with a seven-story affordable apartment tower, but funding hasn’t come through to move the project forward.

Meanwhile, Seattle Mennonite Church in Lake City bought its properties using a donation in the 1990s, without a clear future plan for their use. The church wanted to build on its work supporting homelessness services and hosting an organized tent encampment. “We don’t have to do it. We want to do it,” said Lee Murray, a member of the church team leading the housing project.

They’ve made some progress. The church and the nonprofit developer Community Roots Housing have detailed plans for 171 units of affordable rental housing, including hard-to-find two- and three-bedroom apartments, plus ground-floor space for the church and small businesses or nonprofits.

The church will sell the land for just under $8 million, less than market rate and about $1 million less than it appraised for—key to making the $108 million project pencil out.

But the project needs a mix of government funding, affordable-housing tax credits and private debt and—as public funds are stretched thin—has not been selected for public funding.

Near Los Angeles, the Episcopal Church of the Blessed Sacrament in Placentia partnered with a nonprofit affordable housing developer – National Community Renaissance, also called National CORE – to develop 65 units for older people. The city’s diocese has a goal of building affordable housing on 25% of its 133 properties.

“We don’t have to do it. We want to do it.”

– Lee Murray, Seattle Mennonite Church, on the decision

to build affordable housing on church property.

In St. Paul, Minn., the Mosaic Christian Community, which is affiliated with the Church of the Nazarene, partnered with an organization called Settled to construct tiny homes on church property, including a bed, loft, kitchen and small closet. Peace Presbyterian Church in Eugene, Oregon, sold its property to the affordable housing nonprofit SquareOne Villages to develop Peace Village, a 70-unit development.

Governing Documents

A church’s governing documents should address when and how the church’s real estate can be sold or altered in a significant way. Such guidelines are essential to protecting the real estate as a major asset. But they can also create frustrating problems. For example, if a church’s governance documents tie real estate matters to an outside authority, such as the parent organization of the wider denomination, local leadership may be limited in its options.

The state where the property is located also impacts the process. As an example, in New York, a court order is needed to sell real property owned by a church (religious corporation).

This requirement is outlined in the New York Religious Corporations Law and the New York Not-for-Profit Corporation Law. The sale of church property needs approval from the Attorney General or the Supreme Court of the relevant judicial district.

Additionally, a court order may be needed to sell church property in certain situations in Ohio. If property has been unclaimed for 20 years, if the trustees are unsure how to dispose of it, or if a public church site and meetinghouse have been abandoned, the trustees can file a petition with the court seeking direction on how to proceed, according to Ohio Revised Code, Section 1715.05. The court will then make an order that protects the rights of all parties involved, including the church, congregation and others with an interest in the property.

“It’s really a state-by-state determination,” said Dan Marshall, senior vice president and general counsel for Old Republic National Title Insurance Co. “Title agents should seek input from their underwriter when handling these types of transactions.”

Underwriting Guidelines

Perhaps the most frustrating and complicated problems that can arise for a church that owns land is uncertainty about the land’s ownership. This can be especially true for churches that have a long history. Land that begins under the ownership of one or more individuals, who hold it in trust on behalf of the church, can get entangled in the personal affairs of the titled owners and their heirs. The owner may have passed away without resolving title, leaving heirs who are unsympathetic to the church or otherwise unavailable.

If title problems aren’t resolved, selling land or using it as collateral for a loan may be difficult or impossible. If the church is the owner, confirm that the church’s organization is accurately described in the property deed. This can be especially important if the church has changed its legal form over time. One significant reason a church might choose to incorporate is to assign the church’s real estate to the corporation, which then owns all of the obligations associated with the land along with the land itself.

Churches typically own land by holding title directly, in a trust or through a property holding company, with the specific structure often depending on the church’s denomination or independence. Independent churches often hold title to their real property directly, meaning the church itself is the legal owner.

Many churches, especially those affiliated with larger denominations, hold title to their property in trust, either for the benefit of the local congregation or the denomination itself. This means the local church acts as a trustee, managing the property for the benefit of the trust beneficiaries.

Some churches, particularly those with multiple locations or complex ownership structures, may use a property holding company to manage their real estate assets.

While churches can exist without being incorporated, incorporation may be necessary for the church to hold title to land. A religious corporation or association and the church whose doctrine it represents can coexist independently. In many jurisdictions, a conveyance to an unincorporated association—such as a church—must be made to its named trustees.

“Any title agent handling this type of transaction will need to decide the organizational structure,” Marshall said. “It’s a combination of looking at the entity and the organizational structure. You also have to look at the church hierarchy.”

In order to be considered marketable, Marshall said title to church property should be vested either in the trustees of the church (unincorporated churches), a corporation (incorporated churches) or in a bishop or other applicable church official (corporation sole churches). Proper documentation showing the church organization and entity status must be provided, according to Marshall. If the original owners can’t be located, then heirs must be found. If the heirs aren’t identified, then a quiet title action can be taken.

Perhaps the most frustrating and complicated problems that can arise for a church that owns land is uncertainty about the land’s ownership.

Title agents managing these transactions also need to make sure there is no reversion, a future interest that gives the original owner the right to resume possession or ownership of the property after the current holder’s rights expire. After a certain amount of time, those types of restrictions fall off because of Marketable Title Acts. In Ohio, it’s 40 years after the last transfer a reversion isn’t included, according to Marshall.

“From an underwriter perspective, title agents need to think if it’s all the property or part of the church’s property, they need to make sure the proper authorized people are signing and that state statutes are being followed,” Marshall said. “It’s a combination of looking at the entity and organization structure. Once you’ve established the legal entities, that determines where you go from there.”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

American Land Title Association – direct link to article

Jeremy Yohe is ALTA’s vice president of communications. He can be reached at jyohe@alta.org